Stan Allen says that infrastructures are understood as systems of monumental scale that make an extraordinary effort to satisfy very specific needs. But what happens when, despite their optimistic intentions, they fail? What happens when their construction is not completed? And above all, what value can bring to the landscape an element of monumental scale, designed to fulfill a specific function and which, paradoxically, has become obsolete?

The project aims to raise and answer these questions

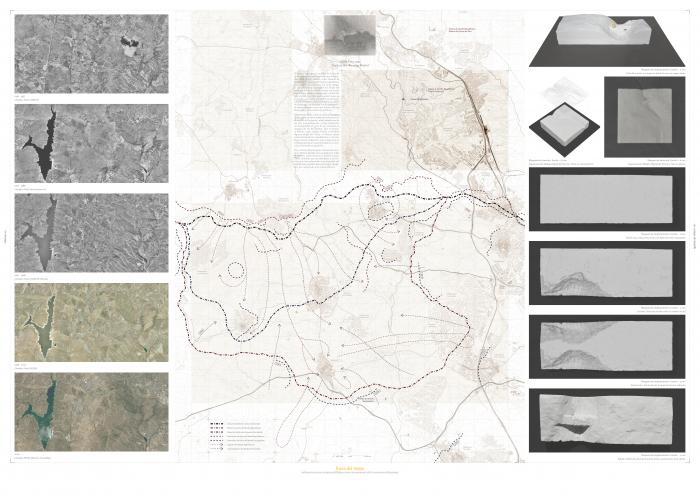

The vertex that joins the municipalities of Torrelodones, Las Rozas and Galapagar is the origin of what is probably the craziest project ever built in Spain: The Guadarrama Canal, a route of almost 700 km long that was intended to connect Madrid with the Atlantic Ocean.

This utopia of granting Madrid an outlet to the sea would not become a reality until the late 18th century, when it began to raise in this location El Gasco Dam, a colossal structure of more than 90 meters high destined to become the highest dam in the world. A dream that, after its structural collapse during its construction, ended up being the tomb of a frustrated project, victim of its own ambition.

In 1937, the Republican offensive that would unleash the Battle of Brunete was prepared from this same location. This one stood out, besides for its crudeness, for its international diffusion through the photographs of Robert Capa and Gerda Taro. Photographs that, although they were printed in our memory, would be lost in a suitcase that was missing for 60 years.

The project, an archive of landscape’s memory, is born with a double purpose: to recover and store the vestiges of these two events; and to exhibit them, to make them no longer belong to anyone but to all of us. In this way, the aim is to make these two stories visible through their legacy in order to make them coincide, not only in space, but also in time. It does not pretend to be an architectural imposition that remedies the situation of oblivion of a place in decline; but rather a new stage in its history which offers an unprejudiced reading of an anthropized landscape that is stripped of its romanticism to turn it into a land of opportunity.

When infrastructures fail, the paradox of the obsolescence of the purely pragmatic occurs. In exchange for this loss of functionality they acquire a new condition, opposite of their original nature: a symbolism, a meaning that makes them the visible legacy of a specific period.

Please highlight how the concept/idea can be exemplary in this context

From the point of view of sustainability, the project strategies could be divided into two groups. On the one hand, passive design criteria, which aim to take advantage of the elements that make up the project in favor of a more efficient thermodynamic behavior; and, on the other hand, active systems, which, although they will be necessary to a certain extent, will take advantage of renewable energy sources to avoid a large environmental impact.

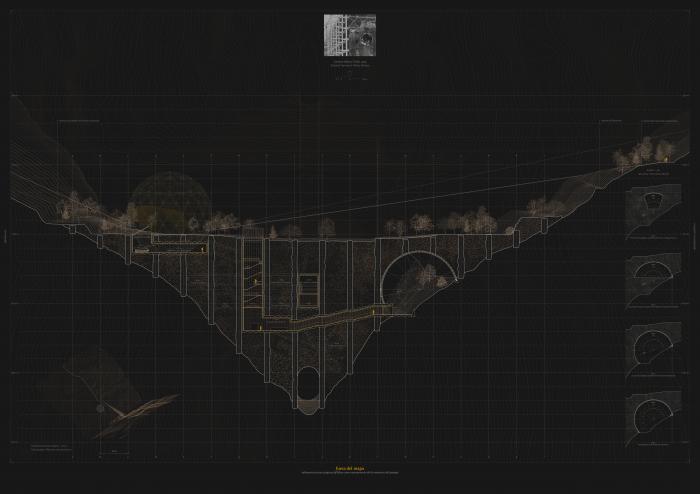

Within the first group is the decision to locate most of the project program inside the dam, underground. This means, firstly, a great material saving, since the remains of something that was already built are reused and, secondly, it also implies energy savings, thanks to the fact that the high thermal inertia of the dam guarantees a practically constant temperature inside the archive with hardly any need for active air-conditioning systems. In this way, the surface area of the project in contact with the exterior is reduced to a minimum, guaranteeing comfort and habitability in a sustainable manner and at a low energy cost.

As for the second group, the active air conditioning strategy on which the project is based is aerothermal energy, which takes advantage of the temperature of the outside air to generate cold or heat, as appropriate, and incorporates it into the ventilation system inside the building. This system is understood as a complement, necessary because the project program, an archive, requires it, since certain temperature conditions must be guaranteed for the preservation of historical documents such as photographs and plans related to the construction of the dam.

In this way, the link between energy efficiency and sustainability is sought, understanding that the approach to the project facilities is not something that is added a posteriori, but is incorporated into the design of the project from its earliest stages.

Please highlight how the concept/idea can be exemplary in this context

The project, an archive of the memory of the landscape, is born as the union between two stories that, although they did not happen at the same time, they did happen in the same place: the construction of the El Gasco Dam and the outbreak of the Battle of Brunete. The program has a double objective: on the one hand, to recover and store the vestiges of these two events, and on the other hand, to exhibit them, so that they cease to belong to no one and come to belong to all of us.

To archive is to keep and maintain, to protect. It is to try to make something last. It is instinctive, when something is in danger we hide it from the sight of others, we hide it, we bury it. Bunkers, treasure chests or our loved ones. Everything seems to become eternal when placed underground.

And this is precisely what is done. A series of voids are generated inside the dam that take advantage of the 10 meters that separate the axes of its tying walls to house the different rooms of the project. The logic of the volumes is always the same: pieces with variable depth and height depending on their use, but with a constant width, connected to each other by a second order of elements that configure the interior circulations. This generates a route resulting from this interplay of volumes, with spaces that compress the visitor's gaze and then expand it, both vertically and horizontally, both in plan and in section.

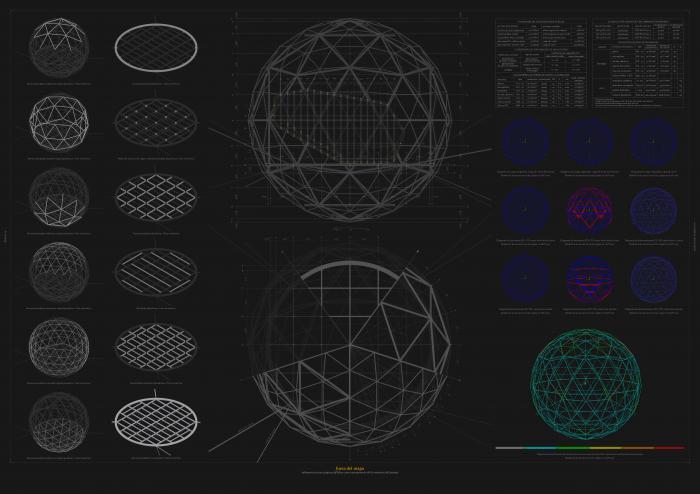

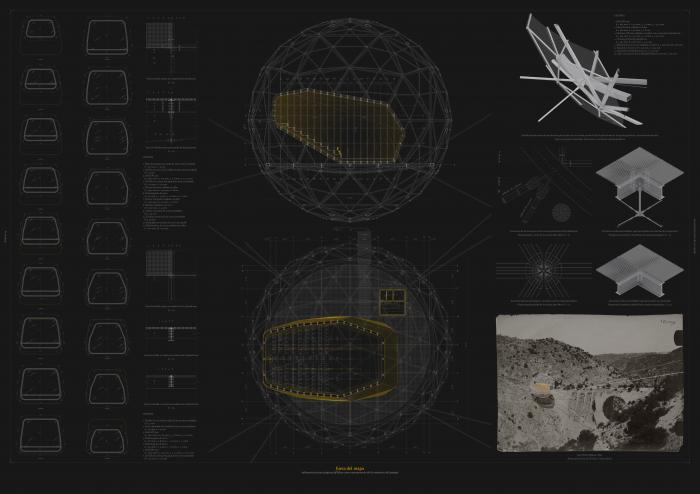

If the scale of the spaces inside the dam is related to the scale of the objects that are stored, in the case of the exterior dome the situation is almost the reverse: to respond to the landscape. The introversion of the archive contrasts with the monumentality and artifice of the dome, which is intended to be shown precisely in this way, as an artifact that summarizes the contradictory essence of the project.

In this way, the intention is to make these two stories visible through their legacy in order to make them coincide, not only in space, but also in time.

Please highlight how the concept/idea can be exemplary in this context

From the point of view of social inclusion, the project has a very clear objective, which is to recover a ruin that belongs to all of us and that, paradoxically, was forgotten, obsolete and relocated in a lost place, like an island in the territory.

It is precisely this insular condition that the project aims to respond to when it investigates questions such as the concept of ruin, the idea of monument or the social conception of landscape, intrinsically related to the memory of the place and its historical and cultural interest. The purpose of creating an archive linked to a given territory seeks to vindicate its cultural value, in contrast to the imposition of other architectures that have been proposed in the surroundings, completely apart from these issues.

This produces a paradox between the insular condition of the project and the hyper connectivity posed by the surrounding infrastructures, such as the Guadarrama River itself, the A-6 highway, the railroad network that runs parallel to it, or the M-505 road, all close to the dam, but nevertheless built on the margins of it, aggravating its disconnection with its immediate surroundings.

The project, therefore, aims to put a focus on a place that is still an urban landscape, understood as a territory of opportunity to offer a critical reading of our past and the construction of the landscape, understanding the impact caused by infrastructures not only from a functional point of view, but also from the perspective of the cultural and symbolic value they confer to the environment.

Please highlight how this approach can be exemplary

It could be said that the project proposes a triple dimension that addresses from the architectural point of view: a cultural dimension, based on the value of the landscape and infrastructure when it acquires the condition of ruin-monument; a social dimension, which seeks to recover the sense of identity and make visible a legacy that belongs to us; and a third dimension based on sustainability criteria, which proposes the convergence of the two previous ones to make them compatible with a sustainable development committed to the environment.

A new symbol is thus given to this place in which a space is created to preserve its history, but also to make it visible and to provoke reflection on it. In this way, an atmosphere of thought is created, warm and intimate, with a cultural, public and social character that moves away from the traditional idea of an archive as a place where information is simply accumulated, to come closer to the concept of a library, a space in which to get back in touch with a not so distant past.

The contemporary idea of landscape as cultural infrastructure is thus made compatible with the concept of territory as palimpsest, which understands this place not as a datum but as a medium in constant transformation, as a superimposition of layers in which history, landscape, society, culture and territory converge.

The features that most significantly show the innovative character of the project are, on the one hand, its positioning in relation to the contemporary idea of landscape and, on the other hand, its structural and constructive development.

From the conceptual point of view, it is based on the ideas put forward by Robert Smithson in the 1960s in his article "The Monuments of Passaic", where he defines concepts such as “cultural landscape” or “ruin-monument”. For him, the idea of monument corresponds to a series of infrastructural remains that, although they have become obsolete, paradoxically continue to contribute a cultural value to the landscape that testifies to a technology, resources and, in short, a philosophy of a particular time and place. The idea of ruin is thus stripped of its traditional romantic character to understand it as a process, as an element that gives added value to the place and ends up defining it and building its memory.

In terms of construction, the most innovative part of the project is the geodesic dome that is suspended from the slopes of the valley to contain the conference room. Its structure consists, firstly, of a platform made up of a grid of beams and brackets stiffened by a perimeter profile and supported by a tensegrity system that minimizes the deformations caused by the cables from which it hangs. Secondly, the dome actually consists of two concentric geodesic domes that allow the exterior space to be covered by a metal mesh that serves as an envelope. Finally, the conference room is resolved by a sequence of transverse ribs tied longitudinally by two other orders of profiles that form a semi-monocoque type structure.

A structure is thus proposed with the constructive logic of the industrialized in which the contemporaneity of the project is manifested, not only from the constructive point of view, but also from its theoretical positioning in relation to the landscape in which it is located.

Given that the project is located exactly at the vertex that joins the municipalities of Torrelodones, Las Rozas and Galapagar, the first measure considered was to contact those responsible for the culture department of each of the municipalities, in order to propose a public exhibition so that the inhabitants of each municipality can get to know the project and thus understand the scope of the project and the reading it establishes with the place. It has already received the approval of one of them and is awaiting a response from the other two councilors of culture.

As it is evident, the project is not born with the purpose of being really executed, since, although it has enough coherence and correction from the structural and constructive point of view, its main objective is none other than to provide a new reading of this place and to make it visible. That is why, as a second measure, it will be presented to another series of academic and theoretical awards and competitions to disseminate a topic that may be interesting because of its ability to extrapolate to other similar situations that occur in our country.

Finally, it will be sought to disseminate in other media, such as websites related to architecture, research journals, social networks and small exhibition spaces in which a topic such as the one proposed by the project can have a place.

If the project were to be awarded in the New European Bauhaus Prizes, I would use the money, in the first place, to continue developing my academic and professional career by pursuing a master's degree abroad focused on research topics in architectural projects. I find it very attractive and stimulating to think about architecture as a tool for thinking through the project process, and I believe that the approach of the work presented finds its main virtue precisely in that question.

Secondly, the award would allow me to establish myself as an independent professional, and I could combine my professional practice as an architect with research and also with teaching, since I am a guest lecturer at the university on numerous occasions. In this way, I would have more freedom to continue developing this and other research that I have done previously, closely related to the one I am exhibiting, but also dealing with complementary topics such as social housing or architectural photography.

In short, receiving the award would be a great help and an important stimulus that would allow me to continue to grow professionally and to increase my dedication to the part of architecture that interests me most, which is the research linked to the project process.

@Toribio, 2022

Content licensed to the European Union.